Urban exploration and the idea of Rome

Last summer I spent some time in Rome. I stayed with architect friends at the heart of the tourist corridor, five minutes away from Piazza Navona. I had not been in Rome for fifteen years, and found it just as I remembered it: eternal and eternally falling apart, divine and pagan, with its sordid back alleys and its splendid basilicas. Rome is an idea made into a city —an idea that has lasted for a thousand years.

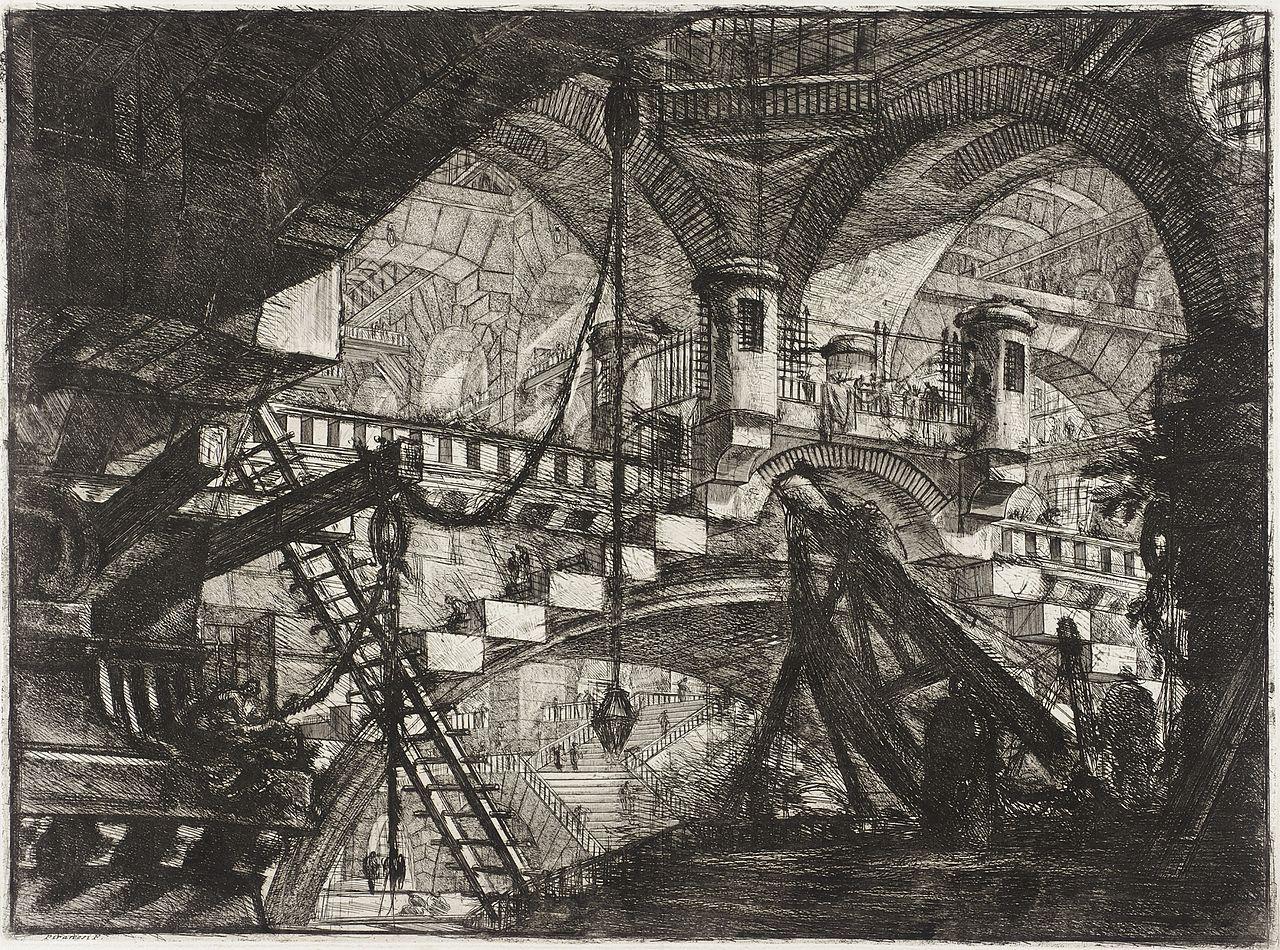

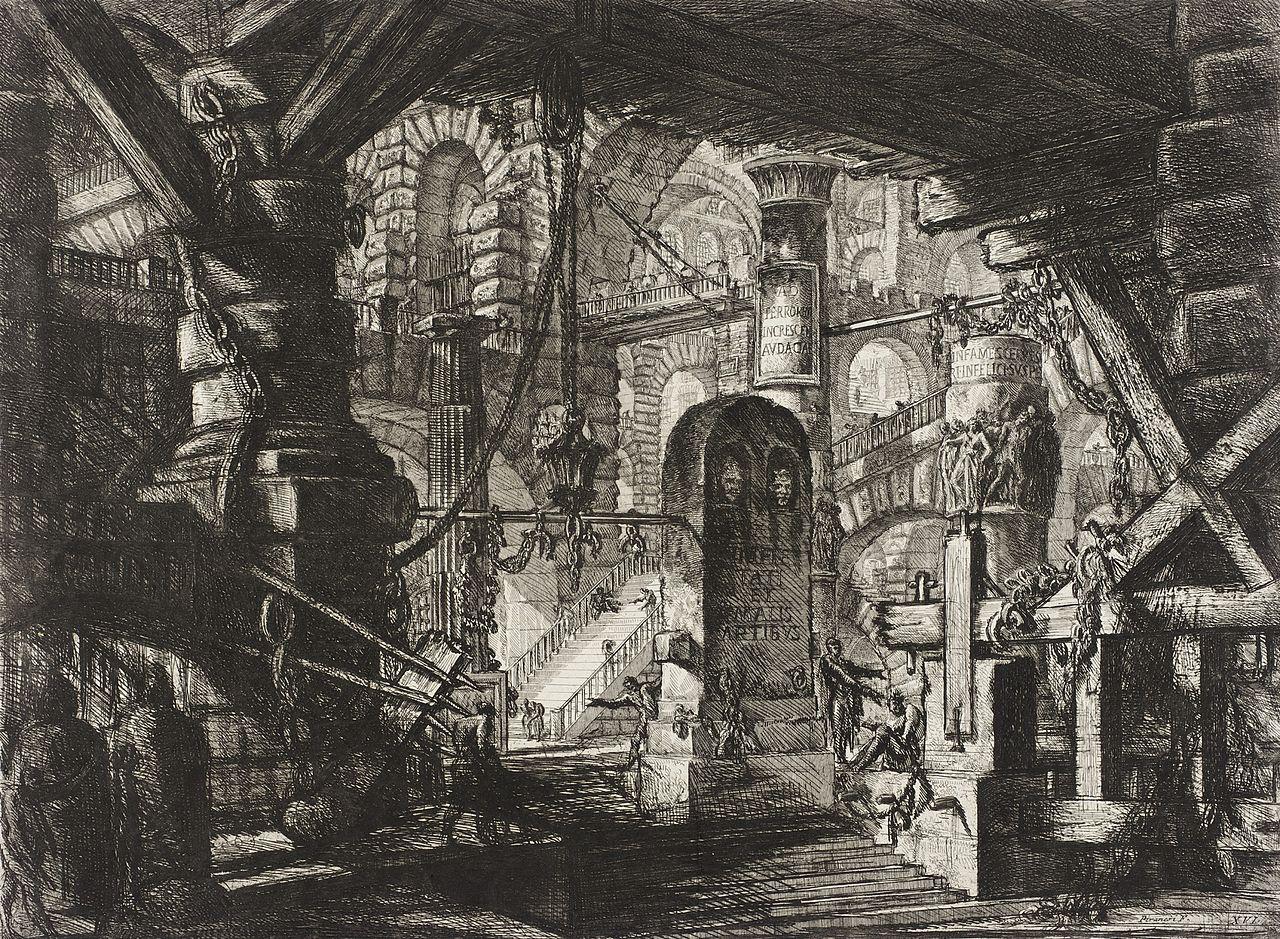

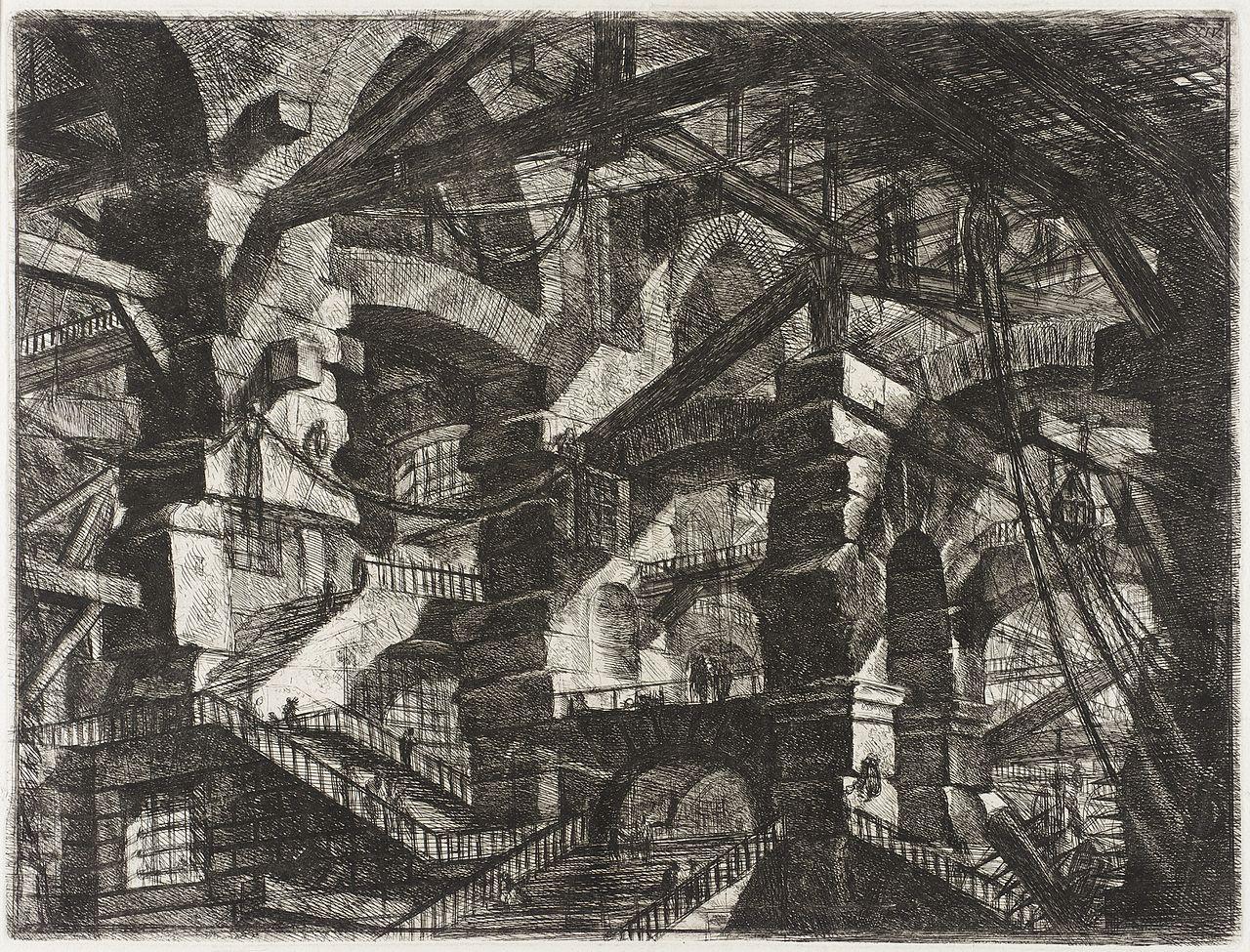

At the museum of Rome I went to an exhibition on Giambattista Piranesi, a venetian son of a stonemason who fell in love with Rome as an idea. Although he called himself an architect, Piranesi didn’t get to build anything in his lifetime, and I suspect he would have remained relatively unknown had the spirit of romanticism not salvaged his architecture of the imagination. Today he is mostly known for his Careceri d-invenzione —a series of sixteen etchings of imaginary prisons; lost and forgotten dungeons of enormous subterranean vaults and dark, labyrinthine, spaces.1

Of special interest to me was a 3D rendering of the Carceri created ex professo by PERCRO lab of the Institute of Communication Information and Perception Technologies of Sant’Anna School of Advanced Study. Part of the allure of the prisons is that, particularly in their second edition, the etchings seem to incorporate elements of spatial inconsistency, so I was curious to see how they would be rendered in 3D.2 Piranesis’s dungeons had been previously reimagined in 2.5D (see below 👇), but I imagined the constraints of stereoscopic modelling would likely expose the paradoxical spaces…

In the end I was rather disappointed with the 3D experience but very impressed by the rest of the exhibition, which highlighted Piranesi’s enthusiasm for roman architecture, urban planning and design. Piranesi’s etchings of fake ruins are not archaeological records of buildings, but rather tokens of revisionist architecture which explore Rome as an idea and an ideal. Perhaps this is the reasons the Carceri resonated with romanticism, and why fake ruins still have aesthetic appeal in contemporary culture. With this in mind, and inspired by the architect of imagination, I set off on a long walk of ruin exploration along the banks of the Tiber during my last day in Rome.

I started south, at the Cimitero Acattolico, where I paid a visit to another famous Italian who once wrote:

“I feel the pulse of the activity of the future city that those on my side are building is alive in their conscience.”

Seeking this social pulse of the city, I ventured into Ostiense and Garabatella, where found some modern ruins, but I couldn’t visit this site without being noticed, so I decided to move on.

I turned north and climbed the Aventine hill through meandering streets and large old houses covered in vines. I was looking for Piranesi’s final resting place, the church of Santa Maria del Priorato, which he himself had helped to restore. Eventually I found it at the top o the hill, close to the basilica di Santa Sabina all’Aventino, but unfortunately Piranesi’s tomb is not open to the public and can only be visited by appointment (I never found where or to whom these appointments needed to be requested, maybe the ancient order of the Knights of Malta has a secret website).

Making my way up the Tiber, and right before Isola Tiberina, I caught a glimpse of the remainings of Ponte Rotto (broken bridge), a 2nd century bridge in a typically Piranesian stay of decay.3

I then found a set of stairs at street level and went down to the river bank sidewalks, where I took this picture:

This was not such a great idea. The person in the photograph whom I mistook for a tourist turned out to be a very angry homeless man who immediately started shouting at me and calling for reinforcements. Soon a group of very upset Italian vagrants showed up and came towards me. It got pretty tense so I retreated.

As I continued north along the river bank, the day gave way into the afternoon and I still hadn’t explored any ruins. My last hope was an abandoned stadium north of the city, in Flaminio. I hired a bike to get there and cycled at good pace along the Tiber.

I found the stadium shortly before sunset, cycled around it looking for a way in and eventually came across a hole in the fence.

A few kilometers south, the crowds must have been gathering around the Colosseum but I had this other amphitheatre all to myself. I had found my own beautiful ruin of the modern just sitting there, partially hidden from the main road by overgrown vegetation.4

I explored for a while, soon it got dark and as I was preparing to leave I noticed a police car by the broken fence. I waited for a while, but the car wouldn’t move, so I moved along and jumped the fence away from the main road and cut myself in the process. By the time I was supposed to meet my friends at the MAXXI museum, I was tired, hungry, bleeding and covered in dirt. A sharp contrast with the slick lines and clean surfaces around me.

The MAXXI was designed by Zaha Hadid, who according to my friends is somewhat of a demigodess of global architecture. I have to say I find her designs suspiciously devoid of social struggle and political conflict; they lack, or perhaps more precisely, appear to lack, a moral dimension to them. The smooth curves and invisible couplings perversely conceal the traces of assemblage, and ultimately, of human labour. I wonder what would Piranesi make of these spaces? Maybe one day the MAXXI will be a ruin too, and someone will then ask what were we thinking, what was our idea of Rome in the early twentieth century.

I also wrote a book chapter about Piranesi’s Carceri and videogames where I trace his prisons to earlier traditions of the Italian vedutistas, particularly Giovanni Tiepolo and Marco Ricci, who established the idea of the capriccio in landscape painting in the early XVII century. ↩︎

The original series was comprised of fourteen etchings and was published circa 1750, but there was a second edition, published in 1761, in which Piranesi added two more etchings (II and V), and re-worked all the others. This is especially significant because in the second edition he seems to have incorporated elements of spatial inconsistency, later picked up by the romantics as early expressions of the Kantian sublime. Cnf: Chris Mortensen (2007). ↩︎

The actual name is Ponte Emilio, and it is quite possibly the oldest bridge in Rome. ↩︎

Not very high quality footage as the light was fading quickly. Here is a gallery with all the pictures. ↩︎